Capital sentencing schemes that permit judges to impose a death sentence despite the votes of one or more jurors for life create a heightened risk that an innocent person will be wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death, according to a new Death Penalty Information Center analysis of death-row exoneration data.

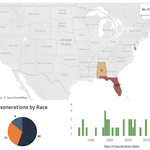

DPIC found that one or more jurors had voted for life in more than 90% of the death-row exonerations in states that permitted judges to impose death sentences based on a jury’s non-unanimous sentencing recommendations or allowed them to override jury votes for life. The three states that allowed those practices—Florida, Alabama, and Delaware—collectively account for one-fifth of all the death-row exonerations since capital punishment resumed in the United States in 1972.

DPIC was able to determine the jury vote in 30 of the 32 exonerations arising out of death sentences imposed in those states since 1972. In 28 of the 30 cases for which the jury vote is known — an astounding 93.3% — at least one juror had voted for life. DPIC was unable to find information on the jury vote for one 1974 conviction in Florida and a defendant in one Alabama case had waived his right to a sentencing jury.

“Death sentences imposed by judges without the unanimous assent of jurors have long been controversial, and for good reason,” said DPIC Executive Director Robert Dunham, who conducted the analysis. “They arose as a means to disenfranchise minority jurors and they often have been applied in an arbitrary, discriminatory, and politicized manner. That they also appear to create a significantly heightened risk that innocent people will be sentenced to death should be an important additional consideration in deciding whether this outlier practice should be permitted to continue or should be abandoned.”

Since 2015, six former death-row prisoners who were sentenced to death by judges despite juror votes for life have been exonerated: Derral Hodgkins (2015), Ralph Wright (2017), Clemente Aguirre-Jarquin (2018), and Clifford Williams (2019) in Florida, Anthony Ray Hinton (2015) in Alabama, and Isaiah McCoy (2017) in Delaware. (Click here to enlarge photo montage.)

Alabama executed Nathaniel Woods March 5, 2020, despite a strong claim of innocence and undisputed evidence that he was not the shooter. Two jurors had voted to spare his life. It also executed Domineque Ray on February 7, 2019, with no physical evidence that he was even present at the scene of the murder. The prosecution had withheld evidence that the only person who implicated Ray in the murder was severely mentally ill and psychotic. The jury voted 11 – 1 to recommend that Ray be sentenced to death. Rocky Myers, who has a strong case of innocence and intellectual disability and received a 9 – 3 jury recommendation for life, also faces imminent execution.

Paul Hildwin was released from prison in Florida on March 9, 2020 after spending nearly 34 years incarcerated for a murder DNA evidence now shows he did not commit. Despite overwhelming evidence of innocence and a Florida Supreme Court opinion stating he would probably be acquitted on retrial, Florida prosecutors intended to retry Hildwin unless he accepted a plea deal for his release.

Prior studies have shown that the availability of judicial override and death sentences imposed by judges based on non-unanimous jury votes produce disproportionately large numbers of death sentences. A 2015 study by the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School and DPIC’s 2015 Year End Report found that more than a quarter of the death sentences imposed in the first six years of the 2010s came from the three judicial override/non-unanimous jury states. More than three-quarters of the death sentences imposed in those states during that time involved non-unanimous jury votes for death.

The Data — Exonerations in Florida, Alabama, and Delaware

Florida. The 29 death-row exonerations in Florida since 1973 are the most in the nation, as are the 25 exonerations in cases tried since Furman. Allowing judges to impose death sentences despite one of more jurors voting for life is a major reason why.

For 24 of the 25 death-row exonerations involving Florida’s post-Furman judicial override/non-unanimity statute, we know whether judges imposed death sentences despite one or more jurors choosing life. In those 24 cases, juries unanimously recommended death only twice. 22 times, one or more jurors voted for life, including four instances in which judges overrode jury recommendations for life.

Alabama. Six former death-row prisoners have been exonerated in Alabama after post-Furman death sentences. At least one juror voted for life in each of the exonerations in which sentencing juries were impaneled. In three of the cases, judges overrode jury recommendations for life — Larry Randal Padgett (9 – 3 jury vote for life); Daniel Wade Moore (8 – 4 for life); and Walter McMillian (7 – 5 for life). Two other wrongfully convicted death-row prisoners, Anthony Ray Hinton and Wesley Quick, were sentenced to death after non-unanimous sentencing recommendations by their juries. The other Alabama death-row exoneree, Gary Drinkard, waived jury sentencing altogether.

Delaware. There has been one post-Furman death-row exoneration in Delaware. Isaiah McCoy was sentenced to death by his trial judge following the jury’s 10 – 2 sentencing recommendation for death.

Name | Year of Conviction | Year of Exoneration | Jury Vote (Death) | Jury Vote (Life Override) |

Alabama | ||||

Anthony Hinton | 1985 | 2015 | 10 – 2 | |

Walter McMillian | 1988 | 1993 | 7 – 5 | |

Randal Padgett | 1992 | 1997 | 9 – 3 | |

Gary Drinkard | 1995 | 2001 | Waived jury | |

Wesley Quick | 1997 | 2003 | 11 – 1 | |

Daniel Moore | 2002 | 2009 | 8 – 4 | |

Delaware | ||||

Isaiah McCoy | 2012 | 2017 | 10 – 2 | |

Florida | ||||

Delbert Tibbs | 1974 | 1977 | Unknown | |

Joseph Brown | 1974 | 1987 | 9 – 3 | |

Clifford Williams | 1976 | 2019 | Unknown for Life | |

Anthony Peek | 1978 | 1987 | 9 – 3 | |

Annibal Jaramillo | 1981 | 1982 | Unanimous for Life | |

Anthony Brown | 1983 | 1986 | Unknown for Life | |

Juan Ramos | 1983 | 1987 | 11 – 1 | |

Willie Brown | 1983 | 1988 | 9 – 3 | |

Larry Troy | 1983 | 1988 | 9 – 3 | |

Juan Melendez | 1984 | 2002 | 9 – 3 | |

Frank Smith | 1986 | 2000 | Unanimous for Death | |

Rudolph Holton | 1986 | 2003 | 7 – 5 | |

Robert Cox | 1988 | 1989 | 7 – 5 | |

Bradley Scott | 1988 | 1991 | 8 – 4 | |

Andrew Golden | 1991 | 1994 | 8 – 4 | |

Robert Hayes | 1991 | 1997 | 10 – 2 | |

Joseph Green | 1993 | 2000 | 9 – 3 | |

Joaquin Martinez | 1997 | 2001 | 9 – 3 | |

Seth Penalver | 1999 | 2012 | Unanimous for Death | |

John Ballard | 2003 | 2006 | 9 – 3 | |

Herman Lindsey | 2006 | 2009 | 8 – 4 | |

Clemente Aguirre-Jarquin | 2006 | 2018 | 9 — 3 | |

Carl Dausch | 2011 | 2014 | 9 — 3 | |

Derral Hodgkins | 2013 | 2015 | 7 – 5 | |

Ralph Wright | 2014 | 2017 | 7 – 5 | |

The Current Status of Judicial Override and Non-Unanimity Death-Sentencing Statutes

Three death-penalty states permitted judges to impose death sentences by overriding jury votes for life or by basing their death sentences on non-unanimous jury recommendations for death: Florida, Alabama, and Delaware. (To see how other states handle non-unanimous jury sentencing votes, see Life Verdict or Hung Jury? How States Treat Non-Unanimous Jury Votes in Capital-Sentencing Proceedings.)

That changed in 2016 after the United States Supreme Court struck down Florida’s death-penalty statute in Hurst v. Florida, declaring that a capital defendant’s Sixth Amendment right to trial by jury requires “a jury, not a judge, to find each fact necessary to impose a sentence of death.” The Delaware and Florida supreme courts responded by ruling that a unanimous jury verdict for death was constitutionally required by the Sixth Amendment and/or state constitutional jury guarantees.

The Delaware Supreme Court was the first to act, declaring its capital sentencing procedures unconstitutional on August 2, 2016 in Rauf v. State. Four members of the court ruled that the state’s capital sentencing statute unconstitutionally empowered judges, rather than jurors, to decide whether the prosecution had proven the existence of the aggravating circumstances that are a prerequisite to imposing the death penalty. They wrote that the Sixth Amendment required a unanimous jury determination of those facts, beyond a reasonable doubt, before the court could consider imposing a death sentence.

A narrower 3‑justice majority of the court also ruled that the facts necessary to impose a death penalty in Delaware included a finding that aggravating circumstances outweigh the mitigating circumstances offered by the defendant as reasons to spare his or her life. Delaware’s statute violated the Sixth Amendment, they wrote, because it did not require that jurors unanimously agree that aggravating circumstances outweigh mitigation beyond a reasonable doubt.

In December 2016, the state court ruled in Powell v. State that its decision in Rauf applied to everyone sentenced to death in Delaware, effectively clearing the state’s death row. The court’s action judicially abolished both judicial override and death verdicts based on non-unanimous jury votes.

In response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Hurst, the Florida legislature amended its death-penalty statute in March 2016 to require that juries unanimously find at least one aggravating circumstance beyond a reasonable doubt and that at least ten jurors vote for death before the trial judge may consider imposing a death sentence. When Alabama then repealed the judicial override provisions in its capital punishment statute in 2017, it ended the practice in the United States. However, the death-penalty amendments in both states applied only to future cases, and prisoners already sentenced to death by judicial override are still subject to execution.

In October 2016, in Hurst v. State and Perry v. State, the Florida Supreme Court declared the state legislature’s revision of the state’s capital sentencing statute unconstitutional because it did not require a unanimous jury recommendation of death as a precondition for imposing a death sentence. In March 2017, the Florida legislature amended the law to require a unanimous jury vote for death before the trial judge may consider imposing the death penalty.

The Florida legislature’s decision left Alabama as the only state to permit judges to base a death sentence on a jury’s non-unanimous sentencing recommendation. On January 23, 2020, a newly appointed conservative majority on Florida Supreme Court receded from decisions in Hurst and Perry requiring jury unanimity, signaling its willingness to uphold legislation reintroducing judicial override and non-unanimous death sentences. However, Florida legislative leaders have indicated that they have no intention at present to return to those prior practices.

— Robert Brett Dunham

March 13, 2020

[Updated March 14, 2020 to include the then-current status of judicial override and non-unanimity statutes.]

[Follow up: In the Spring of 2023, in response to a 9 – 3 jury vote that resulted in a life verdict in the Parkland school shooting case, Governor Ron DeSantis called for a return to jury non-unanimity. DeSantis proposed, and the legislature passed, an 8 – 4 jury vote for death — the lowest standard in the nation — as the threshold at which the trial judge could impose a death sentence.]

Innocence

Mar 12, 2025

Courts Put Upcoming Texas, Louisiana Executions on Hold

Sentencing Alternatives

Feb 11, 2025